Come On Scott Alexander, Obviously The Purpose Of A System Is Sometimes What It Does

What is the purpose of this post? Well, what does it do?

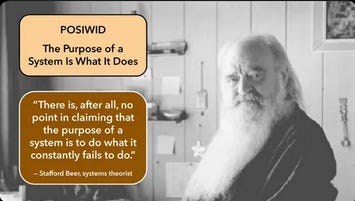

Scott Alexander wrote a blog post titled, ‘Come On, Obviously the Purpose Of A System Is Not What It Does’. I hope the title of this piece plainly telegraphs that I do not think this is so obvious, and wish to defend the contrary view — that often, analysing the purpose of a system in terms of its behaviour is a useful heuristic.

Scott’s post considers some systems and some things they do, and notes that it is “obviously false” that the observed outcomes reflect the purposes of the given systems:

The purpose of a cancer hospital is to cure two-thirds of cancer patients.

The purpose of the Ukrainian military is to get stuck in a years-long stalemate with Russia.

The purpose of the British government is to propose a controversial new sentencing policy, stand firm in the face of protests for a while, then cave in after slightly larger protests and agree not to pass the policy after all.

The purpose of the New York bus system is to emit four billion pounds of carbon dioxide.

He then considers the possibility that these types of cases are not what people have in mind when they assert that the purpose of a system is what it does (POSIWID); so for good measure, he “searched the phrase on X/Twitter to see how people were using it in the wild”. It transpired that the random social media posters were being quite stupid, so he confidently concludes that there can be no sensible uses of the phrase after all.

In my shock and surprise that the usually-so-reasonable random posters on X/Twitter could be so sloppy, I shall engage no further with these examples. However, I did in the comments take issue with Scott’s examples, and used them to explain why and when POSIWID can be a useful heuristic:

I think POSIWID is best applied to bureaucracies or large structures where the reason bad outcomes occur is not because of difficult battles with reality (like government or hospitals or the Ukrainian military), but because of the way incentives are set up in the system.

If someone said, “the purpose of the Civil Service is to drive through new, innovative ways of delivering rapid change!”, that would clearly be absurd. That may be their goal, or how they see themselves; but the purpose of the system is not defined by either of those things. If it was, they wouldn’t incentivise caution and slowness. Whether that’s good or not, the purpose of the Civil Service is best approximated by what it does!

In other words, I agree that sometimes people invoke this heuristic in support of baseless conspiracies, by attributing Everything That Happens to malicious intent and failing to notice that sometimes bad outcomes are just the result of incompetence, limited resources, or bad luck. Curing cancer is hard!

But there are other occasions when outcomes are in fact strongly linked with the institutional structure of the system — what it incentivises agents within it to do, what it penalises them for, and so on. In these cases, it is reasonable to understand the purpose of the system in terms of the actual outcomes it creates, because the system could, by changing its structure, actually obtain different outcomes.

This is in contrast to the strawmen examples1 Scott gives: there is not much the Ukrainian military could change to be more effective in their war with Russia, so the stalemate is a consequence of hard constraints and the presence of a powerful adversary. If there were systemic changes they could make to massively increase their chance of success, it would be reasonable to wonder if the stated purpose of military effectiveness was the actual purpose. It is quite possible for a military to be set up in a bad way that fails to achieve this end; its purpose might practically be to confer status on certain elites, for instance.

Scott responds to my line of argument by noting my use of the word “goal”. He claims that this is synonymous with “purpose”, and thus in conceding that, “[Driving innovative change] may be their goal”, I have unwittingly conceded defeat:

It sounds like Aashish think [sic] it’s useful to use the word “goal” to discuss what a system is trying to do, separately from what it does or doesn’t accomplish. I agree! I just think “purpose” is a synonym for goal.

If you use POSIWID, you have to posit some kind of weird new ontology where “purpose” means the opposite of “goal”. If you don’t use POSIWID, you can just keep the words “purpose” and “goal” having their regular everyday meaning, and describe this state of affairs with phrases like “The goal/purpose of the Civil Service is to deliver rapid change, but due to perverse incentives, its actual effect is to prevent change.”

But I don’t think I’ve claimed — or need to claim — that “purpose means the opposite of goal”. I’m just not convinced they’re interchangeable in this context. There’s a short proof of this: “goals” are properties of individuals, grounded in their mental states; “purposes” are properties of systems. Systems are not necessarily individuals. QED.

The issue at stake is simply whether it makes more sense to identify the purpose of the system with the goals of some relevant individuals (like an institution’s leaders or founders), or with what it actually does. I do agree that sometimes the purpose of a system can be identified with someone’s goals! This happens when some individual has a large degree of control over the system, like a CEO over a small company or a dictator over a state apparatus. But that’s because that person’s goals are unusually effective at shaping the system’s design, incentives, and outputs — that is, what it does.

But if we think goals are what ultimately matter in general, we run into a problem: it isn’t clear which set of goals should be taken to constitute the system’s purpose. The founders may have had one vision, and the current leaders another. Those within the institution may pursue a mix of personal advancement, idealistic reform, or bureaucratic maintenance. These goals often diverge and conflict; is the purpose of the system some muddled average of their goals that no individual actually holds?

Though I’ve now explained why I don’t think it usually makes sense to identify “purpose” with “goal”, I haven’t yet explained what distinct meaning “purpose” I think actually has. In particular, I haven’t distinguished it from “behaviour” or “function”.2

To do that, it might be useful to remember that the POSIWID heuristic has its origin in cybernetics. A foundational3 article in that field, “Behavior, Purpose and Teleology”, by Arturo Rosenblueth, Norbert Wiener, and Julian Bigelow provides a definition of these terms that fit their “regular everyday meaning”:

[T]he behavioristic approach consists in the examination of the output of the object and of the relations of this output to the input… [it] omits the specific structure and the intrinsic organization of the object. This omission is fundamental because on it is based the distinction between the behavioristic and the alternative functional method of study. In a functional analysis, as opposed to a behavioristic approach, the main goal is the intrinsic organization of the entity studied, its structure and its properties.

Or to rephrase: “behaviour” is the short-hand for what a system actually does; “function” is what a system is — a holistic account of its internal organisation and mechanisms that tells us how its behaviour would vary across different environments.

Where does purpose fit into this picture? One way to think about what we mean by “purpose” is that we’re asking, “what is this system for?” What role does it play in the broader ecology of systems that it’s embedded in? What outcomes does it reliably produce, and if it didn’t exist, what would be different?

Evidently, analysing anyone’s intentions is usually not going to be a productive way of answering these questions. Instead, we want to look at the system’s stable pattern of behaviour, which emerges from the way its function interacts with the existing environment. From this, we can infer the implicit justification for the system’s continued existence — what problems does it solve? That is what I mean by purpose.

This is well-understood in other contexts. The purpose of a thermostat is to maintain room temperature. How do we know this? Because its internal mechanisms respond to deviations from a target value, resulting in stable, homeostatic outcomes. The purpose of a bird’s wings is to enable flight. In this case, unlike with the thermostat, nobody had that goal in mind, because nobody designed the wings. But we understand their purpose from what they do.

In the more general case, I claim that it makes more sense to infer the purpose of a system from its function, or what it is, than to identify it with someone’s goals. And sometimes, there is a strong correlation between what it is (incentives, institutional structure, constraints) and what it does (the outcomes it attains). In such cases, inferring purpose from behaviour is a sound heuristic, and one that is useful because analysing all of the internal workings of a system is difficult. It’s a much sounder heuristic than the notion that its purpose can be found in “the intentions of those who design, operate, or promote it”.4

In Scott’s examples, the POSIWID heuristic is less sound because the behaviour of the system is constrained by the sheer difficulty of the problem they’re trying to solve; even an optimally designed system would be unable to cure all cancer patients or win all wars. So we would have to determine the purpose through the more difficult task of directly analysing the structure of the system.

But this isn’t always the case! Often, systems produce bad outcomes because the structure of the system is “designed” (not necessarily consciously) to produce them. And this is important to understand, not to be paranoid or conspiratorial, but because sometimes a better designed system really could produce better outcomes.

POSIWID is not meant to put an end to conversation or replace analysis. It is meant to be a useful starting point for analysis. It isn’t always appropriate, but it often is.5 I see no sense in discarding it wholesale because it fails in edge cases or because it has occasionally been invoked in stupid ways. If that were the standard, we’d probably have to give up on saying anything at all, and sit forever in enlightened silence. Wittgenstein would approve.

I don’t mean to be rude — I like Scott Alexander, to be clear!

Thanks to my friend Oliver Haythorne for pointing out to me that I should distinguish these!

According to Wikipedia; thanks to Joe Litobarski for directing me to this article.

Daniel Litt has noted that I should probably have mentioned some good analyses in terms of POSIWID. I don’t want to edit my post now, but for examples of the kind of thing I had in mind, I’d recommend The Elephant in the Brain: Hidden Motives in Everyday Life, by Robin Hanson & Kevin Simler.

Well written and argued. The point about looking at how a system is situated within a larger system, and considering all the things it does and not just one, is a very important one that Scott left out. Sure the NYC busses produce a lot of exhaust, but the system does a few other things that are kind of important...

My lengthy response, which I turned into a post of my own, can be found here!

https://substack.com/home/post/p-161502045