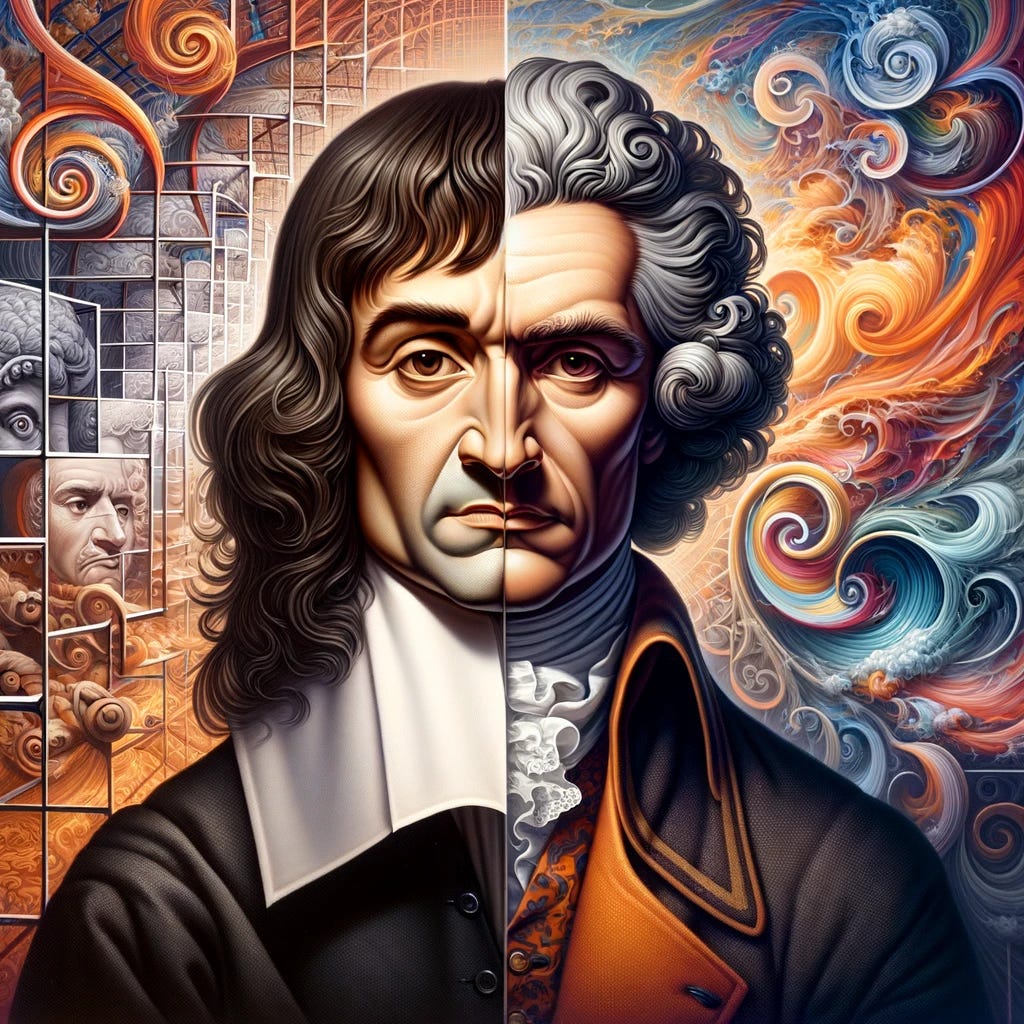

The stimulus shows a person with an ambiguous identity. This may raise the philosophical question of whether that person has a stable and unified identity, or whether his identity comprises more than simply the sum of his experiences (an a priori soul). I shall consider this issue by contrasting Hume’s conception of the self as a ‘bundle of perceptions’ and Descartes’ mind/soul-body dualism, concluding that ultimately both are flawed, with a superior account offered by Henri Bergson.

Descartes wishes to establish the existence of God and the soul on rational grounds, to convince those without faith. He thus employs his method of hyperbolic doubt – he questions all of the principles on which his beliefs rest. After all, our senses sometimes deceive us, so we cannot know whether they are deceiving us in any particular case. Taken to the extreme, he assumes for the sake of argument there might be an evil demon (rather than an all-loving God) who is always deceiving us through our senses. Proceeding in accordance with that hypothesis, he suspends all his beliefs based on sense experience (including that he has a body), and seeks some truth that survives this: that it would be illogical or self-contradictory to doubt.

He concludes that the belief that must survive this process is the belief in one’s own existence. It is absurd to doubt that I exist as a ‘thing that doubts’, without presupposing the existence of the ‘thing’ that doubts. Hence, “I am, I exist” is necessarily true whenever it is stated by me or conceived in my mind. This, for Descartes, is the human self – the ‘thinking thing’, which he identifies with the mind and the eternal soul.

Fearing that the evil demon hypothesis will prevent him from establishing any other truth (thus trapping him in solipsism), Descartes then establishes the truth of God’s existence, drawing upon the idea that he has an idea of perfection in his mind; using the principle that ‘there must be at least as much reality in an efficient and total cause as in the effect’, he argues that he cannot be the cause of his perfection since he is imperfect – so it must have been placed there by a perfect being: God.

He can now discount the evil demon hypothesis as illogical, since a perfect God would not create such an evil being. Humans are strongly inclined to believe that there is a distinction between sense experience and imagination. Since a benevolent God would not give us such a strong inclination to believe something false, then the external world must exist; and as part of the external, the body. Thus Descartes argues that the self is composed of two separate substances: mind (soul), which is eternal, non-physical and non-composite; and body, which is finite, physical, and composite.

However, there are several issues with this ‘substance dualist’ account. One of these is recognised by Descartes, namely the problem of interaction: if the self is composed of two ontologically distinct substances (the corporeal body and the non-corporeal mind), the question of how the two interact is raised – how the mind causes effects on the body. The solution he raises is extremely unsatisfactory, as he simply points to the pineal gland as where this interaction takes place: but since this is physical, this solution simply begs the question.

Descartes’ conception of the self raises several questions. He makes several dubious assumptions: for instance, that each time I conceive of my existence, I am the ‘same’ person (and do not, for example, cease to exist when I am sleeping); and that the ‘I’ is a single thing, rather than many.

Hume raises such questions in presenting his alternative. He criticises the notion that the self is ‘simple’ (non-composite) and ‘identical’ (continuous and unchanging through time). We never perceive ourselves as a simple and identical being; rather, we perceive ourselves as a bundle of different and changing impressions and ideas. Hume argues that there is no underlying substance or essence that unites these impressions and ideas into a coherent self. The self is nothing but a fiction that we create out of habit and imagination. Thus, we have no rational basis for believing in the existence of the self as Descartes conceives it: it is simply a succession of experiences, each of which succeeds the last, like actors continually passing through the theatre stage.

The Cartesian response would note that this conception seems to contradict the evidence of our experiences. Each of us believes and feels as if there is a meaningful sense in which we are the ‘same’ person as we were yesterday. Descartes’ account, arguably unlike Hume’s, is capable of making sense of our own experience as ourselves as persisting through time; it is because we have a soul persisting through our experiences, knitting them together in a single identity.

Although he acknowledges that our natural propensity is to believe Descartes’ claim that there is a simple and identical self that persists through our experiences, Hume argues that this is a fallacy. In particular, it confuses two different ideas of identity: identity in the strict, logical sense of something remaining the same; and identity in the sense of resemblance, in which changes in the object occur so ‘smoothly’ that the imagination presents it to us as a single object (in the sense of the first notion of identity). Our imagination deceives us when we intuit the constant, unchanging self.

Even if we concede this point, it remains that Descartes’ conception of the self at least tries to account for the seeming continuity; Hume’s account, by contrast, is too reductive. By reducing the self to a mere bundle of perceptions, we cannot make sense of our subjective experiences – we cannot simply dismiss this as the bias of our imagination.

As unsatisfactory as Hume’s argument is, violating our intuitions that identity persists through time (arguing that that perception is a fallacy), Descartes’ is equally problematic in the age of science, with his assumptions about humans possessing a soul. In addition, his argument for the existence of God – which is the means through which he ‘escapes’ solipsism is faulty, assuming that an imperfect being could not conceive of (‘cause’) the idea of perfection. Moreover, his proof of the reliability of clear and distinct perceptions is derived from the premise that God is not a deceiver; but this proof presupposes the reliability of his clear and distinct perception of the idea of perfection; so his argument is circular.

Thus Bergson presents a conception of the self that speaks to those who reject both Descartes’ and Hume’s views. He denies that the self is a simple and immutable soul, as Descartes claims, but he also denies that the self is nothing but a bundle of perceptions, as Hume argues. He offers a different way of understanding the self that is based on intuition and duration.

He argues that time is not a measurable quantity that can be divided into discrete units, but a qualitative flow that is continuous and indivisible. He calls this flow duration, and he claims that it is the essence of our inner life. Duration is not something that can be grasped by the intellect, but only by intuition, which is a direct and immediate awareness of our own experience.

Bergson’s notion of duration implies that we are not exactly the same person throughout our lives, but we are also not completely different from ourselves at any moment. We are constantly changing, but we also retain a sense of continuity and identity. This is because our duration is not a mere succession of states, but a dynamic process that involves memory, anticipation, and creativity. We are always creating ourselves anew, but we also carry with us the traces of our past experiences. Our intuition of duration connects us with ourselves across time.

Bergson’s account of the self is thus more complex and nuanced than Descartes’ or Hume’s. He does not reduce the self to a substance or a fiction, but he tries to capture its richness and diversity. He does not rely on abstract concepts or logical arguments, but he appeals to our own experience and intuition. He offers a way of understanding the self that is more faithful to our living, active, and concrete personality; and thus, it provides a better way to understand the self than either Hume or Descartes.